economist.com

MORELOS AND QUERÉTARO

TWENTY years ago Juan Morales shut his beautifully preserved 19th-century mill in Morelos, a village in Coahuila close to the Texan border, after reductions to subsidies made the flour business unprofitable. Now he hopes the mill will get a new lease of life, thanks to a historic energy reform by President Enrique Peña Nieto (pictured). Instead of producing flour, Mr Morales plans to generate electricity, using water from his millstream and a newly acquired power turbine. For the first time he will be able to sell it to the local grid.

Until now, almost all electricity in the country has been generated by the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE), a state monopoly whose smoke-belching plants in Nava, ten miles (16km) away, guzzle so much coal that there are huge tailbacks of the sooty lorries that deliver it. Like Mr Morales, the CFE has its eyes on a brighter future. According to its boss, Enrique Ochoa, the energy reform will enable it to become more than just an electricity giant.

For the first time it will be able to sell natural gas to private-sector users—a business previously reserved for Pemex, the state oil monopoly. It will build up to seven new gas-fired power plants to cut down on the use of dirty and expensive fuel oil. It will also provide long-term gas contracts to foster the creation of a new pipeline network built, owned and operated by private firms. Mr Ochoa wants Mexico to look like Texas, which is one-third the size of Mexico but has seven times as many natural-gas pipelines. Already pipeline projects worth $2.2 billion have been announced. “It’s going to be marvellous,” he beams.

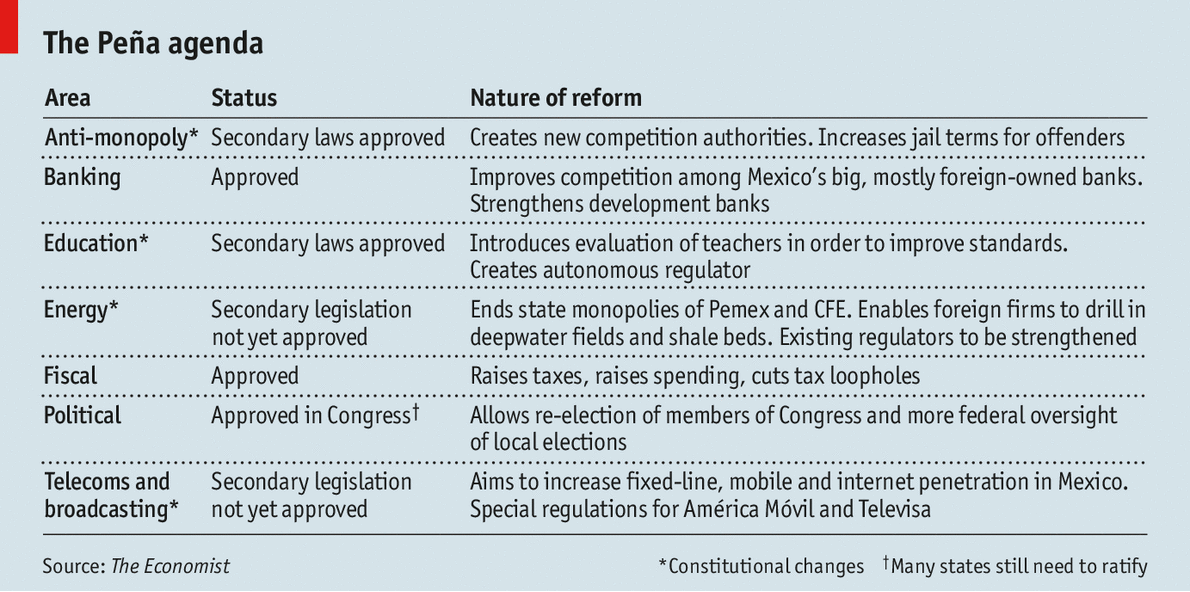

Mexico’s energy overhaul is the crown jewel in a programme of seven reforms (see table) undertaken by Mr Peña since he took office in late 2012. The energy reform is partly about drilling for hydrocarbons. Oil majors are already salivating at the thought of an end to Pemex’s 76-year-old monopoly, and of reversing a decade-long slump in oil production; others are focused on new sources of energy, such as shale oil and gas. But the biggest prize is cheaper electricity.

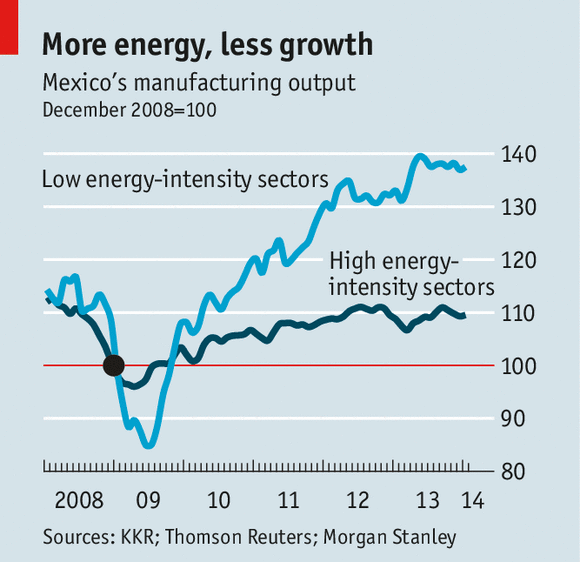

Mexico is already a manufacturing powerhouse. It makes almost a quarter of vehicles imported into the United States; on June 27th Japan’s Nissan and Germany’s Daimler said they would spend $1.4 billion to build compact luxury cars in Mexico, coming after a $2 billion plant that Nissan opened late last year. But industrial electricity costs are almost 80% higher than in the United States, which means that energy-intensive industries, like plastics and metals, have not done nearly as well as trades like carmaking (see chart). Lower bills would make them much more competitive. “With cheap energy, Mexico will be unstoppable,” says Luis de la Calle, a pro-reform economist.

Few emerging markets can boast a reform agenda as ambitious as Mr Peña’s. Some outsiders put it on a par with Shinzo Abe’s “Abenomics” programme in Japan. Yet the mood in Mexico itself is much more downbeat. An end-of-June deadline for passing secondary laws to flesh out the reforms in energy and telecoms has come and gone as the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) haggles with the opposition. A vote on this legislation is now hoped for later this summer. The economy is crawling along, partly because a tax-collection drive has not been matched by a boost in public spending. Many fret about the capacity of freshly minted regulatory bodies to stand up to the likes of Pemex.

A sense of pessimism prevails even among businessmen well placed to benefit from the reforms. Galo Bertin founded Especialistas en Turbopartes 23 years ago in Querétaro, one of Mexico’s most dynamic cities. His firm repairs turbines used in electricity generation, oil production and manufacturing—the very industries that should benefit most from an energy revolution. Mr Bertin is a rarity in Mexico: a self-made man who has stitched a local business into global supply chains. He proudly shows off a new area of the factory to handle what he expects will be a surge of aerospace orders.

Yet he has grave doubts about the impact of Mr Peña’s reforms on the country at large. Following a tax reform last year, Mr Bertin says his business has ground to a halt for the first time in its life because of finicky rules on payroll and investment that his accountants are still trying to fathom. He ridicules the government’s promise that energy costs will fall. “I bet you lunch that prices won’t come down,” he tells The Economist. Such scepticism is understandable. Mexico has been in the grip of monopolies and duopolies for so long that people know little other than high prices and poor service.

Big business, too, has its misgivings. It is widely rumoured that Carlos Slim, owner of a phone empire that has made him one of the world’s richest men, has stopped investing in his existing telecoms networks in Mexico and is worried that a telecoms-and-broadcasting reform unfairly favours his arch-rival Televisa, the biggest TV company (and a staunch backer of Mr Peña). A plunge in telecoms investment is a big factor behind the economic slowdown.

A movement, not a moment

What is more, businessmen have looked in vain for infrastructure contracts that were supposed to rain down this year. Though the finance ministry has boasted of a surge in money allocated to public spending, hardly any of it has been spent, says Rogelio Ramírez de la O, a consultant. Some accuse Luis Videgaray, the finance minister and brains behind the reforms, of micromanaging public-spending projects too zealously. They hope that a series of big projects, such as a long-awaited new airport for Mexico City, will get under way once the energy reform is completed.

Others still believe the main aim of Mr Peña’s administration is to consolidate central-government power (via a higher tax take and the creation of numerous regulatory bodies) rather than to support free enterprise. As one investment banker puts it, there is a growing concern within the private sector that a cartel of big businessmen is being replaced by an over-powerful gang of politicians.

Supporters of the reforms contend that the complaints from big firms reflect a healthier relationship between the government and the private sector. They note that Mexico has a low tax take relative to other members of the OECD, a rich-country club, partly because big companies have been so good at dodging taxes. “Some of their anger”, one official says, “is that they [were] used to being very close to the government and negotiating with it. This government is hearing them but not negotiating with them.”

Even the squeals of small firms are given short shrift. Though they too have found the fiscal reform tough, government officials say much of the pain is caused by the closure of tax loopholes. They argue that a payoff will come eventually through more business opportunities thanks to the energy and telecoms reforms; cheaper credit via more competitive banks; and less informality as a result of incentives for small firms to register with tax authorities.

The government hopes that the benefits of the reforms—jobs growth, more credit, better education, more oil—will be visible before Mr Peña’s term ends in 2018. Lower electricity bills, the most obvious sign of success, could arrive sooner still if cheap natural gas is imported in greater quantities from the United States, and new sources of power generation are developed in Mexico. With so much riding on the reforms, the last-minute delays in Congress are frustrating. The task of improving productivity in the rump of small businesses is immense; the risk of a fall in oil prices, which would clobber government revenues, is skated over. But when they are finally passed, the benefits of Mr Peña’s programme will outweigh the costs.

No comments:

Post a Comment