MOST of the ogling in Rio de Janeiro happens at the beach. Not so for visitors from Mexico’s energy ministry. On their last visit to Brazil, their covetous eyes fell on the new R&D labs of Petrobras, the country’s state-controlled oil company. Not many miles away from Copabacana beach, the labs are surrounded by international oil companies doing their own high-tech research. Enrique Ochoa, Mexico’s deputy energy minister, hopes that one of the effects of December’s energy reform will be to create such a cluster in Mexico.

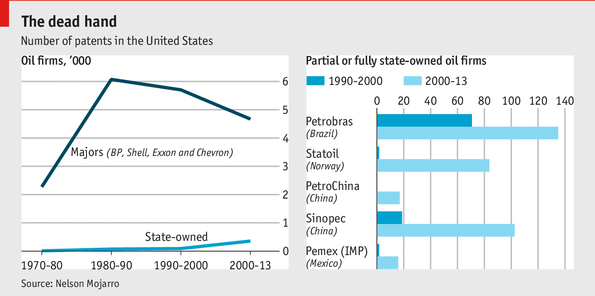

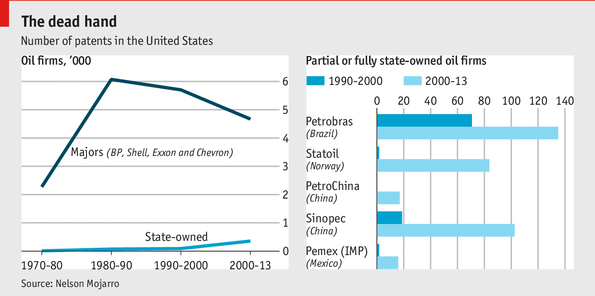

That is a tall order in the short term—and not just because most of the areas where Pemex operates look like grimy ink spots compared with Rio. The charts below are from Nelson Mojarro, a researcher who is affiliated with the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. They show how drastically behind the curve Pemex, Mexico’s oil monopoly, is in terms of innovation. The first one shows how many more patents oil majors generate in the United States compared with state-owned companies (including listed ones like Petrobras). The second shows how far Pemex (via its R&D arm, the Mexican Petroleum Institute) lags even its state-owned peers.

Mr Ochoa, in an interview with The Economist this week, is upbeat. He says that the Brazilians believe Petrobras’s innovative skills improved dramatically once its monopoly ended in 1997. He expects the same to happen to Pemex.

He is also bullish on the outlook for legislation in the next few months to accompany December’s constitutional reforms, which for the first time allow for private contracts and partnerships between Pemex and other companies, ending a 75-year-old monopoly. He says the secondary laws will provide enough flexibility that different royalty and fiscal terms can be written into individual contracts. (He is slightly uncomfortable with the idea that the “government take” should necessarily be around 75%, as other supporters of the reform have suggested.) He also insists that transparency is key, so that all contracts can be scrutinised and the public can see where the money is spent.

Another priority of the secondary legislation will be setting out the parameters for Pemex’s ability to compete and to forge partnerships, like other oil companies. The aim, he says, is to give Pemex more autonomy, a more competitive tax regime, a greater capacity to retain talent, and a board that promotes best international practices. Details are scarce, though.

Pemex will also have the opportunity to form strategic alliances, or even to dump assets if it chooses. Mr Ochoa gives the example of Deer Park, a refinery in Texas operated by Pemex and Royal Dutch/Shell, which is more productive than any of the refineries in Mexico that Pemex operates alone. “Imagine the madness,” says Mr Ochoa. “You could have something that gives you good results in Texas that you could not have in your home territory.” With the reform, he expects Pemex to strike up many such partnerships in businesses such as refining in Mexico. He doubts Pemex will try to exit unprofitable businesses altogether.

The secondary legislation is due to be approved by the end of April. By the end of September it should be clear which oil and gas fields Pemex will develop, and which will be licensed or contracted out to others. But Mr Ochoa does not expect bidding on new fields to begin until the end of 2015 at the earliest. This is partly because time will be needed to train new regulators (he reckons some will come from among Pemex retirees) and to find specialists in drawing up, tendering and adjudicating contracts.

By then, too, it may be clearer where an energy cluster might emerge. Veracruz has already staked its claim to a deep-water research laboratory. Let’s hope Tamaulipas, a northeastern state riven by narco violence, also gets a look in. It is badly in need of a brighter future—and sits right next door to one of the bastions of the shale revolution in south Texas.

That is a tall order in the short term—and not just because most of the areas where Pemex operates look like grimy ink spots compared with Rio. The charts below are from Nelson Mojarro, a researcher who is affiliated with the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. They show how drastically behind the curve Pemex, Mexico’s oil monopoly, is in terms of innovation. The first one shows how many more patents oil majors generate in the United States compared with state-owned companies (including listed ones like Petrobras). The second shows how far Pemex (via its R&D arm, the Mexican Petroleum Institute) lags even its state-owned peers.

Mr Ochoa, in an interview with The Economist this week, is upbeat. He says that the Brazilians believe Petrobras’s innovative skills improved dramatically once its monopoly ended in 1997. He expects the same to happen to Pemex.

He is also bullish on the outlook for legislation in the next few months to accompany December’s constitutional reforms, which for the first time allow for private contracts and partnerships between Pemex and other companies, ending a 75-year-old monopoly. He says the secondary laws will provide enough flexibility that different royalty and fiscal terms can be written into individual contracts. (He is slightly uncomfortable with the idea that the “government take” should necessarily be around 75%, as other supporters of the reform have suggested.) He also insists that transparency is key, so that all contracts can be scrutinised and the public can see where the money is spent.

Another priority of the secondary legislation will be setting out the parameters for Pemex’s ability to compete and to forge partnerships, like other oil companies. The aim, he says, is to give Pemex more autonomy, a more competitive tax regime, a greater capacity to retain talent, and a board that promotes best international practices. Details are scarce, though.

Pemex will also have the opportunity to form strategic alliances, or even to dump assets if it chooses. Mr Ochoa gives the example of Deer Park, a refinery in Texas operated by Pemex and Royal Dutch/Shell, which is more productive than any of the refineries in Mexico that Pemex operates alone. “Imagine the madness,” says Mr Ochoa. “You could have something that gives you good results in Texas that you could not have in your home territory.” With the reform, he expects Pemex to strike up many such partnerships in businesses such as refining in Mexico. He doubts Pemex will try to exit unprofitable businesses altogether.

The secondary legislation is due to be approved by the end of April. By the end of September it should be clear which oil and gas fields Pemex will develop, and which will be licensed or contracted out to others. But Mr Ochoa does not expect bidding on new fields to begin until the end of 2015 at the earliest. This is partly because time will be needed to train new regulators (he reckons some will come from among Pemex retirees) and to find specialists in drawing up, tendering and adjudicating contracts.

By then, too, it may be clearer where an energy cluster might emerge. Veracruz has already staked its claim to a deep-water research laboratory. Let’s hope Tamaulipas, a northeastern state riven by narco violence, also gets a look in. It is badly in need of a brighter future—and sits right next door to one of the bastions of the shale revolution in south Texas.

No comments:

Post a Comment